So, what is it that I am actually doing here?

I am studying in Copenhagen on a

Valle scholarship, a program created to foster engagement between scholars at the UW and in Scandinavia. It is open to graduate students from UW and from any of the partner schools in Scandinavia or the Baltic States in built environments, civil engineering, and environmental engineering. As an urban planning student I fall within the UW's College of Built Environments, and was able to apply to study in Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania or Denmark. I ultimately applied to conduct an independent study on housing in Copenhagen, Denmark on the advice of a few enthusiastic boosters of that city, and was able to arrange a guest researcher position at Aalborg University's branch here through some luck and generous referals (Thanks Bry!).

My project is to study housing in the context of a "livable", compact city.

Copenhagen is compact. Copenhagen is about two and a half times as densely populated in Seattle. That means the entire population of their city (plus the jobs and parks and infrastructure and everything else) fits into about a third of the area of Seattle. Copenhagen's population is about 6/7 of Seattle's (591,000 / 684,000), so it's pretty close.

That means there is much more room for farms and natural areas surrounding the city. It means more efficient heating and other utilities and less costly public infrastructure. It also means it's much easier to get from one side of the city to another. Transit is good in Copenhagen, but the city's bike lane network is incredible. Cycling is the most popular way to get around the city, accounting for about

45% of all trips. Again, this is possible because the city is, physically, not that large. Together all this makes Copenhagen one of the most sustainable cities in the developed world.

Copenhagen is also renowned for it's "livability". Livability is a peculiar term that refers to how easy and how enjoyable it is to live in a place. It refers to the number and quality of parks, useful and exciting businesses, engaging cultural events and quality of social services that are present and easily accessible in a place. Copenhagen has been ranked #1 globally in livability in

2014, 2013 and 2008. That was by a magazine called "Monocle" which I had never heard of, and I'm not going to pretend this is a rigorous measurement. Still, it means something about how the city is perceived by locals and the global community.

The goal of my project is to profile the housing that supports this relatively high density while maintaining (and/or promoting) such a high standard of urban life. What is it like? How is it laid out? When was it built? Who built it? Why did they design it the way they did? Who owns it? What are the regulations that govern it? How much does it cost?

I want to know these things because I think it is important for Seattle to learn how to be a denser city in the 21st century without degrading our quality of life. Conversations about density in Seattle tend to devolve into nightmare scenarios of New York ghettos or soviet gulags, which is a little bit hilarious, but also unfortunate. Because of our cultural, technological, and historical context out west we are used to a very spread out way of living. This can be nice, but it has real consequences there are other ways of living more compactly that are not like a soviet gulag. This is what I want to learn.

I'm applying these questions to different areas around town. The first neighborhood I've been looking at it the oldest part of the city, called

Indre By ("Inner City" in English {linguistically

I think

by is related to the word "build" in English which in Danish is

bygge. Also the by in "bylaws" comes from the same root.}).

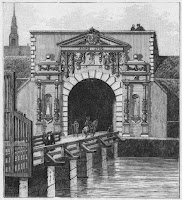

Indre By was the whole city up until about 1850, but was first built up in the late middle ages. It has an excellent natural harbor and strategic location on shipping routes meant that the town grew fairly quickly, and by 1500 it was a walled city with a population of about 5,000.

The walls were expanded during the early 1600's and ultimately demolished in the mid 1800's, but the heart of the city has maintained the small, tight grid of curving serpentine streets and compact public squares of its early days.

The blocks here are small, and they have very high building coverage. Though the street and block pattern of this part of the city dates back to medieval times, the building stock mostly does not. The city burned down twice during the 1700's, and was heavily bombarded by the British during the Napoleonic wars. An old church survives from 1474 and there are a number of houses from the 1600's, including the famous Nyhavn row:

but the most of the buildings in this part of town date from around 1795-1850.

These buildings are blocks of flats that front on the street and have small interior courtyards. Historically the small courtyards in this part of town were used for keep livestock, privies and light industry; today they are mostly used for bicycle parking, storage, utilities and dumpsters. The courtyards provide access to more apartment buildings inside the block called

backbuildings. Almost all buildings are between three and five stories. They tend to be quite compact. On the block I measured, their widths vary between 7.5 and 18 meters wide (about 25 to 60 feet), with an average width of about 12 meters (40 feet). The apartments are reached by stairwells, which typically access two apartments per floor. Larger buildings have multiple stairwells to reach more apartments. Some buildings have been retrofitted with small elevators, but I believe this is uncommon.

The density of windows and entrances, the narrowness of the buildings and their variation in facade color and treatment, the narrowness of the streets, their cobblestone pavement, their liveliness, and the many small businesses all tend to reward the pedestrian with a very stimulating and enjoyable environment. It is visually pleasing as well as mentally stimulating because there are many things going on, and you have to look at each one to try and figure out what it is.

|

| Strædet, one of the first streets that went car-free in Copenhagen |

Many of the streets and squares in this area have been gradually converted to pedestrian-only streets (plus relaxed cyclists). This transformation was spearheaded by the architect and urban planner Jan Gehl, who is the most famous Dane among people like me. Strangely, most Danes have not heard of him. Gehl made his career working on the seemingly obvious idea that people and their experiences matter.

Yesterday I got to join with a group from my university who is in town for two weeks on the "Gehl Studio" trip, in which they will study the city and then try to bring their insights home to apply to a project in the Seattle area. We visited the Gehl Architects office and heard a presentation about their work and methods to document human activity in public places (walking, sitting, playing, talking, watching) and to design places that promote and protect such behavior. Much of it was familiar to me from years as a planning/urban design/active streets nerd, but something about the nature of the common-place, low-intensity behavior that they seek to document means it easily slips out of the front of one's mind.

|

| Before/After: one of the streets in Copenhagen banned to cars |

The work they do to develop clear methods and measurement criteria and to communicate effectively is all the more important for how seemingly mundane the subject is. As they said in the presentation: You must measure what you value. Things like automobile counts, speeds and gas prices are easy to measure and we're used to hearing about them. Measurements yield data and data influences policy, especially because it gives politicians cover when pressed on the results of their spending programs.

What is revolutionary about this method, is a reevaluation of which are the things are truly valued, and make sure that these are the qualities we are measuring and seeking to promote through policy and design. The effect of this philosophy, along with much hard work by Danes whose names I don't know, has yielded a city with exceedingly pleasant qualities to pass through at a slow speed, immerse oneself in its fascinating places, spend time socializing with friends or family, visit as a tourist, or simply to be a person around other people.

It's people-habitat. It's compact and livable. Gehl and others have effectively documented the magic that happens in the streets. But what about that which surrounds the streets, equally as mundane, the places where the walkers and cyclists and shop owners and AirBnB toursits begin and end each day? The boring vernacular architecture of the guts of the city, usually not designed by any architect, but built to fill the needs of the day by craftsman who learned their skills on the job from their more experienced peers. It's form, cost, location, relationship to the neighborhood and type of ownership all bear on how it fulfills its function. Clearly, something about it works well here.

That's what I'm here to learn about.

[Update: Google Photos made this silly video of things I captured during my tour around town with the Gehl Studio group. It's actually kind of cool.]